Inside the Fight at Hillside Villa: Multiracial, Multigenerational Tenants in Chinatown Organize for Housing Justice (KCET)

Over a hundred families live at Hillside Villa Apartments, a 124-unit apartment building in Chinatown, LA that up until recently was subject to a 30-year agreement with the city to house residents at below-market prices. The Hillside Villa Tenants Association (HSVTA) is made up of tenants who are predominantly working class, Latinx and Asian immigrant families, organizing across language barriers and the difficulties of a pandemic. In the past two years, the organizers have witnessed losses from COVID-19 among members of their own community. They keep organizing in the hopes that they can stay together.

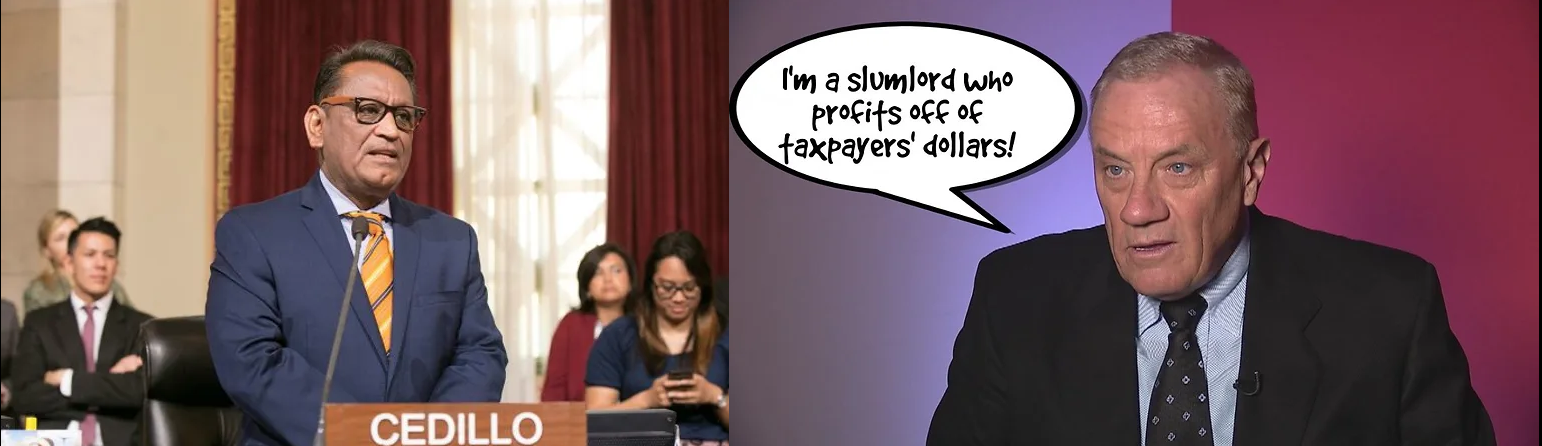

Some of the tenants were previously displaced from their home where the Los Angeles Convention Center currently stands, with the land forcibly taken via eminent domain. And all around them, examples of eminent domain’s use of a tool for displacement take the form of architectural spectacle. For Hillside Villa, eminent domain emerged as a tool of preservation after an attempted deal between landlord Tom Botz and Councilmember Gil Cedillo fell through in 2019.

The Walt Disney Concert Hall and the Los Angeles Convention Center, among other sites of Hillside Tenants’ protests, represent spectacles of public money for private profit, Hillside Villa tenants argue. The cost of the Los Angeles Convention Center was the razing of a low-income, predominantly Latinx community, with reports of displaced residents receiving a meager average of $9,300 as compensation.

“Generally, eminent domain has been used to enrich wealthy people, but never to protect poor people,” Cynthia Strathmann, Director of Strategic Actions for a Just Economy (SAJE) said.

According to a UCLA report, the Walt Disney Concert Hall was a beneficiary of $110 million of county money and built on public land. Eminent domain was a core strategy used by the city to initiate a force-sale of private property for public use, which caused the displacement of hundreds of families in the neighborhood of Bunker Hill.

“The principle of eminent domain is about using public money for public good,” said Annie Shaw, an organizer at the Hillside Villa tenant association and Chinatown Community for Equitable Development (CCED), which along with the Los Angeles Tenants Union (LATU) has teamed up with the Hillside Villa tenant union to organize alongside tenants.

From projecting the neon green words “HCID SHOW US THE $$$$$” onto the modernist steel wings of the Walt Disney Concert Hall, to calling to defund the police at the Los Angeles Police Department (LAPD) Headquarters, Hillside Villa tenants’ protests prompt viewers to think about what purposes the government is prioritizing for the expenditure of public funds while the preservation of uses as essential as homes is up for debate.

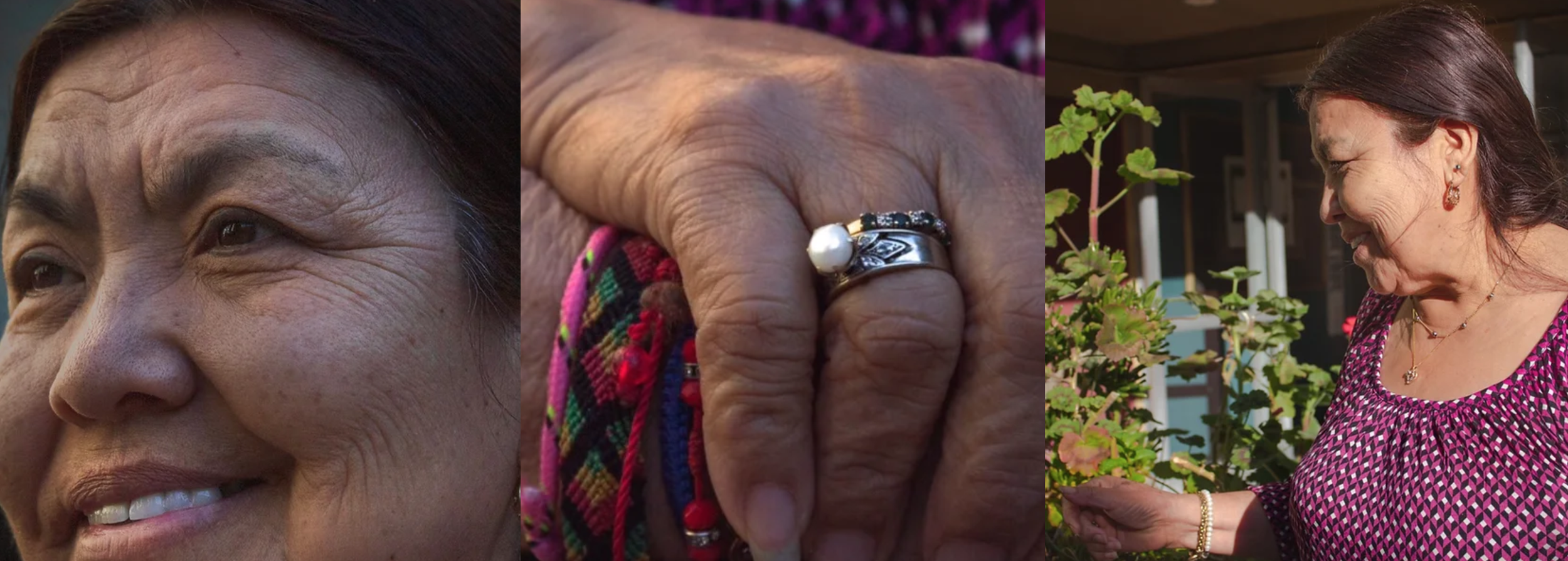

Upon meeting Marina Maalouf, 66, a longtime tenant of Hillside Villa, Maalouf promptly plucked guava from her tree in the courtyard and placed them into my hands. She later offered me the few avocados she had in her home, gifted by a friend, despite Maalouf having food insecurity herself. Even when Maalouf was experiencing extreme financial difficulty during the height of the pandemic, with barely enough food in her apartment to sustain herself, she was thinking of others and sharing what little she had with her neighbors. “Maybe somebody else might need this [food] more than me,” she said.

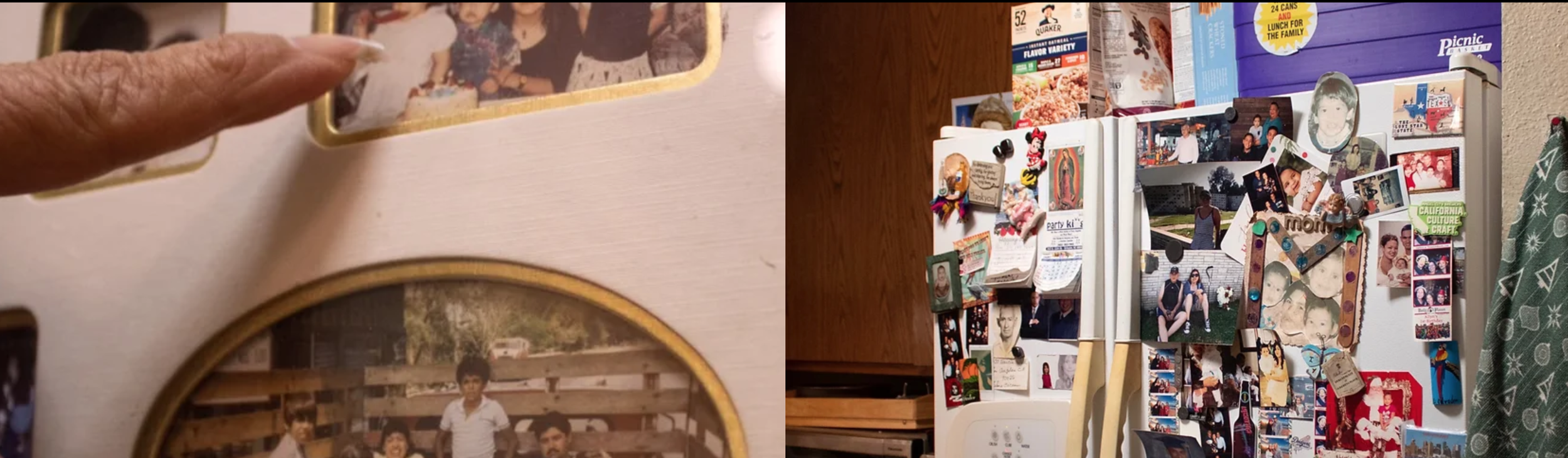

24 years ago, Maalouf found a community in Hillside Villa, where she raised her three children and built long lasting relationships with her neighbors. Maalouf’s home is a physical testimony to her relationship to her community: the walls are alive and overflowing frame-to-frame with photos of family and friends that span decades. She can trace back furniture like the TV and her bed frame to a story of a neighbor who gifted it to her.

“My life is happy, but it’s sometimes sad,” Maalouf said. “But I am glad, you know. I give thanks to God that my family is okay and healthy.”

In the wake of COVID-19, Maalouf was laid off from her job where she cleaned offices. While experiencing unprecedented financial strain, her landlord, Tom Botz, served 200% rent increases to low-income tenants in the name of “executing his right to begin earning his full return on investment.” According to Knock-LA, recently in 2021, two Hillside Villa elders passed away from COVID-19, but the tragedies did not stop Botz and his daughter Chloe Botz from serving three-day notices to tenants whom they alleged owed rent from before the pandemic.

Even before the pandemic, tenants had noticed warning signs of abuse from their landlord. At one point Botz had billed Maalouf for plumbing repairs, she said. According to California law, it is illegal for a landlord to charge tenants for normal wear-and-tear repairs, with plumbing issues being a common landlord repair responsibility. The exception to the rule is when damages are caused by the tenant.

This time, when she was seeing the distress that the landlord was inflicting on not only her, but also her neighbors, she knew she couldn’t stay silent.

“[Tom Botz] is greedy with the people here, and he doesn’t care about us. That’s why I started with the tenant association,” Maalouf said. “Because I always like to be right with people, to be fair with people, you know?”

THE PUBLIC DISPUTE BETWEEN THE CITY AND LANDLORD

The demand for eminent domain was born out of a long road of tenant organizing and failed attempts at negotiation between the city – Councilmember Gil Cedillo – and the landlord, Tom Botz.

According to Curbed LA, in July 2019, Councilmember Cedillo had announced to tenants that he and Botz had come to an agreement stipulating that Botz would extend the affordable covenant for another ten years in exchange for the city waiving the debt that Botz still owed to the city on the building. However, Tom Botz “reneged” on the deal and served 5.5 percent rent increases to tenants, effective September 1, 2019, almost immediately after Cedillo’s announcement, which Cedillo described as an act of “bad faith” and responded to ongoing pressure from Hillside Villa tenants by launching the motion for the city to purchase the building through eminent domain.

In an interview with Hillside Villa landlord Tom Botz, Botz said the 2019 deal was never finalized, despite media portrayals. According to Botz, he and Cedillo disagreed on the “principal amount of debt” owed to the city. When legal issues arose, Cedillo’s office evaded “the details” and went cold on him, Botz said.

“He talks a nice game, but when it came to it, he didn’t want to deal with the details,” Botz said. “There’s a lot of detail work involved.”

In a statement to KCET from Councilmember Cedillo’s office, Director of Communications Conrado Terrazas-Cross emphasized the Councilmember’s commitment to preserving affordable housing units in his district, with Hillside Villa being a prominent effort. Councilmember Cedillo’s district ranks number one (2,243 units from 2009-2020) in the number of affordable housing units permitted among all the city council districts – while facing great precarity, with slated losses of 3,700 affordable units expiring across Los Angeles between 2021 and the end of 2023, according to the city’s Housing and Community Investment Department.

“Councilmember Cedillo’s goal is to not displace any tenant from their affordable housing unit,” Terrazas-Cross said.

Botz thinks that the city has neglected the tenants and believes the responsibility of ensuring housing for low-income families should be on the city – not on him as an individual landlord.

“[The city] left us holding the bag with the tenants, and we said to the tenants, ‘we’ve been preparing for this for 30 years,’” Botz said.

Botz said that if Cedillo is committed to housing the tenants who paid affordable rent for the last three decades, Cedillo should “fast track” the tenants to Section 8 government-subsidized housing. In that case, Botz would be happy to keep longtime tenants in the building.

Under Section 8, the landlord charges market-rate rents, tenants pay a maximum of 30% of their incomes, and the Housing Authority makes up the difference to the landlord.

Botz prides himself on welcoming Section 8 – unlike other landlords in Los Angeles, he notes – despite the fact that it is illegal for landlords to discriminate against Section 8 tenants. He discussed how Section 8 ensures that he makes market-rate on each unit in the building. Botz gave an example of how a tenant would pay $1,500 in one case, and the city would pay the other $1,500 “like clockwork” – totaling in a monthly $3,000 that ensures Botz a market-rate return. Botz said that at the moment, his building is majority Section 8, with that amount having risen since 2019 when he first served 200% rent increases to his non-Section 8 tenants. Tenants who moved out in the last few years were replaced with new Section 8 tenants, increasing the total number of Section 8 tenants that make up the building now.

“This is not a building where we’re mandated to have Section 8 tenants,” Botz said. “[But] every vacancy we get, we try to fill with section 8 tenants.”

Annie Shaw, an organizer at Chinatown Community for Equitable Development argues that Botz filling his building with Section 8 tenants and threatening non-Section 8 tenants with eviction is a strategy for him to build wealth off of public money while evading real financial investment in the building and his tenants. Shaw described the status of market-rate as a “veneer” when landlords are not actually renovating the building to be competitive for market-rate tenants.

“The market doesn’t even think his building is worth [3,000 dollars a month],” Shaw said. “The city is bleeding money to subsidize all of his Section 8.”

Even among luxury market-rate apartments identified by community groups as culprits of gentrification such as Jia Apartments, Lllewelyn, and Blossom Plaza built in Chinatown that seek high-earning patrons to live there, attracting market-rate tenants is competitive, resulting in many of the units sitting vacant – a stark juxtaposition to the notorious, years-long waiting lists for affordable housing. Luxury apartment buildings often promise amenities such a gym, full-service reception, a pool, among other resources that are noticeably absent at Hillside Villa, to tenants paying upwards of $3,000 a month for a 2-bedroom apartment in Chinatown.

The waitlist for a Section 8 voucher is also reportedly obscenely long, with a 2017 LAist article clocking in the number of Section 8 applicants at over 40,000 Angelenos.

“It's not easy to apply for Section 8,” Hillside Villa tenant leader Leslie Hernandez said during a coalitional livestream of housing justice organizations across Los Angeles, Families United: Housing by Any Means Necessary. “It takes ten years plus, just to get a voucher.”

Shaw also emphasized that maintenance and repairs are the bare minimum responsibilities of a landlord – not benevolent acts of generosity. According to Shaw, Botz only began renovating units after the covenant expired, but those were minimal “mickey-mouse renovations,” such as new flooring, or a new screen. There have been reports of rat infestation in the building and in one case, tenants who suffered a broken pipe that flooded their unit were denied a relocation unit and forced to live under conditions of mold, damp floors, and putrid smells for weeks. Botz lamented in the interview that tenants requested “condo-style” remodeling from him when he introduced 200% rent increases but denied that he was remodeling units contingent upon tenants paying more. According to Shaw, for most longtime working class tenants, they had been living in the same untouched unit for over thirty years.

“He’s implying that if you’re low-income you have to live in slum conditions,” Shaw said.

Botz is aware of the spotlight that has been directed at his building in the wake of the organizing for eminent domain, noting that he’s had to hire an extra person to “deal with” the problems at the building and expressing that it has been expensive. Shaw suspects that Botz is gearing up for the fight and making renovations that have come decades too late in the lead-up to the city deciding exactly how much it will offer him for the building.

“The tenants are hardworking, working class people trying to survive. No one’s getting rich living in Tom Botz’s building. People are just trying to survive. But he gets to be rich and sponsored.” Annie Shaw, CCED Organizer

As of right now, about 40 families in the building are on rent strike and protected by the eviction moratorium as they continue to organize and await decisions from the city.

“[Cedillo’s] turned us against each other and he’s created this rent strike and we think he’s supporting it,” Botz said, describing how he believes his relationships with the tenants has become increasingly adversarial over the years, especially accompanied by what he believes to be antagonism from public figures like Cedillo.

“Cedillo supports the Hillside tenants' activism and has fiercely advocated on their behalf to preserve their affordable rents,” Terrazas-Cross said. “Hillside Villa tenants have every right to organize and be active in their struggle to keep the affordability of their rents and prevent displacement or homelessness.”

When responding to questions of whether or not Botz would consider a compromise to keep non-Section 8 tenants housed, Botz said he’s been “supporting the tenants for 30 years,” and said under state law, he had to give one-and-a-half year of notices before threatening eviction if tenants cannot pay the 200% rent increase, claiming that tenants have had ample time to make arrangements.

While the time frame appears lawful, the last three to four years have actually been needlessly tumultuous for tenants, as Botz served illegal rent increases that incited panic as soon as the covenant expired. Botz called this a “technical error.” He had served rent increases early (in 2018) on an expired covenant and was subsequently sued and forced to rescind eviction notices and rent increases to comply with California’s state preservation notice law (Botz re-issued 12-month notices in September of 2019 compliant with state law). Additionally, Knock-LA reported that these increases also violated Gov. Gavin Newsom’s December 2019 law stipulating that landlords cannot increase rents by more than 10% through the year of 2020 due to protections for wildfire recovery. Botz also described his singular meeting with the Hillside Villa Tenants Association at the beginning of their organizing as “pointless” because “tenants said they’re not interested in the rent increases.”

“All the things we’ve been working for for 30 years and we’ve projected are down the drain,” Botz said. “It's a nightmare. It's a total nightmare.”

Organizers and tenant union members, however, push back against Botz’s complaints about his failure to make his full return. People are trying to make ends meet – unlike Botz, there are no millions of dollars waiting for them at the end of this fight, Shaw said.

“The tenants are hardworking, working class people trying to survive,” Shaw said. “No one’s getting rich living in Tom Botz’s building. People are just trying to survive. But he gets to be rich and sponsored.”

Anahy Hernandez, one of the tenant leaders, said she sees the physical and emotional toll that this struggle has taken on her community.

“A lot of people are already tired, you know, from capitalism,” Hernandez said. “You know, work, family, like having to take care of your family, and I think having very little money to pursue anything that you might want to. I guess Hillside Villa has empowered us to come together… and to demand a change.”

Maalouf’s fighting spirit traces back to her youth in El Salvador. When she was just 14 years old, she gathered tomatoes, chilies, cranberries, cilantros, onions, radishes, and cabbage from her family’s farm in a basket to hand out to local community organizers in secret. She always wanted to help her people, she said, despite how her father warned her against doing so. At the time, there was a violent civil war brewing in their country. She immigrated to the U.S. in her youth for safety, with her family fearing that any relationship to the leftist organizers in her hometown could risk her life.

Maalouf continues to care for her community to this day, tending to papaya, lemongrass, guava, and chili plants, among others, in the courtyard of Hillside Villa, to share with her neighbors.

Just as her personal home tells stories of relationships built over decades of living at Hillside Villa, the public gathering spaces in the building have historically represented the presence of community in the building. They used to have well-loved communal staples like seesaws for kids and outdoor grills for family gatherings in the courtyard; these were removed by Botz and the building management in the last few years.

Maloouf says removal of communal property like this has become commonplace in the last few years. She said the landlord uprooted the rose gardens she cultivated in recent years, leaving giant, hollow concrete ditches, which Maalouf views as safety hazards for kids. Management brought in new additions to the courtyard space – a security camera and “no skateboarding” signs. According to Knock-LA and testimonies from tenants, the landlord’s daughter has been seen personally patrolling the hallways and scolding kids for playing or making noise in the building. Tenants have reported a broken elevator in the building that poses a major accessibility risk to elderly and disabled tenants. According to tenant testimonies, the manager responded that it will get fixed “when tenants pay rent.”

“I remember all the ladies, sitting right there, talking and talking. That was nice, but all those days, they are gone. All those good days are no more.” Marina Maalouf, HSV Tenant

According to Cynthia Strathmann, executive director at Strategic Actions for a Just Economy (SAJE), the “overweening” emphasis on landlords’ private property rights allows landlords to take liberties in infringing upon tenants’ rights to a peaceful home. Strathmann likened the tenant-landlord relationship to other rental services, such as that of Avis and Hertz car rentals. Whereas most other rental industries prioritize customer service, when it comes to profit-driven housing, some landlords feel absolved of the responsibility to provide a peaceful home for their tenants.

“If you rent a car, people would be incensed if Avis or Hertz guy followed you around seeing what you're going to do with the car,” Strathmann said. “Yet for some reason, when you rent that apartment, the landlords often still feel like they have some kind of proprietary rights to it, even though they have rented it to someone else. They took money in exchange for that person's control of that space, and they need to abide by that contract.”

Tenants like Maalouf remember a time before rampant surveillance by their landlord and before longtime neighbors were pressured to move out by management.

“I remember …all the ladies, sitting right there, talking and talking,” Maalouf said, reminiscing on how the residents used to gather in the courtyard. “That was nice, but all those days, they are gone. All those good days are no more.”

Still, longtime tenants like Maalouf took it upon themselves to water and regrow the communal plants in their apartment building courtyard.

The story of Hillside Villa is also one of re-birth; emerging from within the tenant association, second-generation voices that carry on the fighting spirit of older immigrant generations. This “second-generation wisdom,” coined by Anahy Hernandez, is a renowned determination to navigate and expose the violence of structures – legal, political, economic – historically designed to exclude their families.

Younger generations of children, now adults, who grew up at Hillside Villa and watched their parents forge tight-knit bonds, are stepping up to use their voices in the fight to keep their families safe and together in the home they’ve always known.

Leslie Hernandez, a tenant leader in the Hillside Villa tenant association, has lived at Hillside Villa since she was five years old. She is 36 now. She said seeing the pain of the immigrant women who helped raise her, receiving thousand-dollar rent increases, was too much to bear.

“Living here, honestly, gives me the feeling of having family around,” Hernandez said. “I know I can count a lot on these ladies. It hurt me to see them crying, to worry about what's going to happen to them.”

Hernandez talked about seeing their manager speak patronizingly to immigrant tenants for whom English was not their first language and police tenants for the smallest acts, like watering the courtyard plants, or feeding stray cats. She also saw how the landlord took advantage of the fact that tenants did not know their rights and could not read the rent increase letters, only the alarming increase in numbers – according to Capital and Main, in one tenant’s case, $800 to $1,950.

“I’m a loudmouth,” Hernandez said. “I’m a very loud person naturally, so I told myself, if I have a voice, I need to use it for these people. I need to use it for my family—my Hillside family.”

Hernandez loved growing up in Chinatown. She said back in the day, people would say that if you could drive in Chinatown – the busiest, most crowded of streets – you could drive anywhere in Los Angeles.

Now, it feels like a “deserted town,” she said. The gentrification of Chinatown over the last decade has wiped familiar community members from the landscape and replaced bustling streets with luxury developments that cater to wealthy demographics. The majority of places she frequented as a youth are gone now – she can no longer take her goddaughter to them, she said. What also hurts, she said, is seeing the city approve the mass influx of luxury developments that remind all the working class residents that they do not deserve communities to call their own “because they are poor.”

“I didn't think that mini-mall was going to be demolished, you know,” Hernandez said. “Just to see Chinatown changing and it's all because of these developers coming in and just not caring [...] All they see is money signs, all they see is the land and they’re like, how can we exploit it?”

Most recently, Chinatown has been swept by unrest amid news that the last legacy shopping center in Chinatown, Dynasty Center, was purchased by Santa Monica developer Redcar. Redcar is the same developer that purchased the Chinatown Swap Meet building with the intent of converting it to an architectural office space. Chinatown community organizers at CCED have also sued developer Atlas Capital for their proposal of a 700-unit mixed-use apartment complex with zero affordable housing. The gentrification of Chinatown, whether through the loss of stores for immigrant families to shop and attain basic necessities, or the development of multi million-dollar luxury housing complexes, whittle away real physical mobility and access to resources for longtime immigrant, working class families living in Chinatown.

Just to see Chinatown changing and it's all because of these developers coming in and just not caring... all they see is money signs, all they see is the land and they’re like, how can we exploit it?” Leslie Hernandez, HSV Tenant

According to Cynthia Strathmann of SAJE, the private housing market means real estate speculation for many, but determines whether or not everyday people can have a roof over their heads.

“All of these [landlords], you know, their primary goal, in a way, isn't to provide housing, their primary goal is to make money,” Strathmann said. “And they'll provide housing as an avenue to making money, but when they can't make money, they're not going to provide the housing.”

Anahy Hernandez, 26, who is one of youngest members of the Hillside Villa Tenants Association, first watched her mom become involved in the Tenants Association. Much of her inspiration for her organizing, showing up to protests and meetings after long days of work, comes from her mother.

THE SECOND GENERATION IN CHINATOWN

“A mother’s first instinct is to provide shelter,” Hernandez said. “Us as children, we see and feel these injustices, but we can’t make it logical, because as kids and teens there’s only so much we know.”

Hernandez said she did her own research and discovered that cash for keys, without informing tenants of their rights and following certain regulations, is illegal – despite how she often saw Botz use the tactic to harass her neighbors. She said that landlords like Botz capitalize on various factors, including tenants not having money for lawyers, or lack of educational background to undergo bureaucratic processes. But Anahy Hernandez made it clear that this fight for housing is connected to larger systemic factors – race, gender, socioeconomic status, immigration, education – and larger historical processes that have created the power dynamic that she and her family are fighting back against now.

“Whether we like it or not, like this is also politics,” Hernandez said. “And this is very wrapped up with our identities too, as you know, Black, Indigenous, and people of color (BIPOC). We don't choose this. The system chooses this for us and that's why we're standing up and fighting against it.”

For Anahy and Leslie, a lot of the determination to win this fight stems from the love that their families passed down to them as children. Leslie takes care of many children in the building and has emphasized how children are predisposed to the stress of adults around them.

“That's why we fight — because we love our families,” Anahy Hernandez said. “We don’t want to see everyone go through hardships. Having to get up and leave your entire family to move because of an eviction is violent. But in that, we are also sacrificing ourselves, and putting our bodies on the line to get to the end goal.”

"We don't choose this. The system chooses this for us and that's why we're standing up and fighting against it.” Anahy Hernandez, HSV Tenant